Recent 3D films: Twittering Soul, Westermann, Lateral, Photosynthesis

Compared to the dry spell of the previous few years—I know of no natively 3D films that premiered in 2020 or 2021, and only two (Avatar 2 and A Woman Escapes) from 2022—the last year and a half have been relatively rich. I’ve written some about Anselm (a bad documentary with some good 3D shots of installation art) and Laberint Sequences (one of the two or three best films of last year), and will probably write more on the latter soon whenever MUBI’s 3D program featuring it and other Blake Williams films finally releases.

But there have been four more films in the last six months. A couple of these are fairly minor, but still worthwhile, shorts. Charlie Shackleton’s Lateral was screened at First Look this year, and is more of a loose lecture accompanying demonstration through images than a fully realized film in its own right. 3D imagery is most often made by shooting simultaneously with two cameras spaced apart and then showing those images, respectively, to the left and right eyes, allowing the brain to process them as three-dimensional much in the way our ordinary vision does. Shackleton notes that you can accomplish nearly the same thing by moving a camera quickly sideways, and then allowing the images to repeat with a very small lag. Since this camera movement already happens in any number of films, he tests and demonstrates the idea by reanimating footage from a number of classics, beginning with Akerman’s D’Est but also including The Shining and so on.

The technique is surprisingly effective. The resulting 3D has limitations in that there are some strange ghostly artefacts around human movement, and the images flatten as the camera slows or stops, but they mostly look quite convincing. Of course, Shackleton is not the first to have this idea, and he acknowledges that others experimented with this technique a century earlier, though only at the end of his film and he doesn’t engage with the specific work of others, like Ken Jacobs, who have explored the technique to more artistic ends. The technique has limited practical application, as it mostly offers no advantage over filming natively in 3D with two cameras. What’s more interesting about the film is the questions it asks about how our vision already works, and about what information is already contained in the “2D” images of any film.

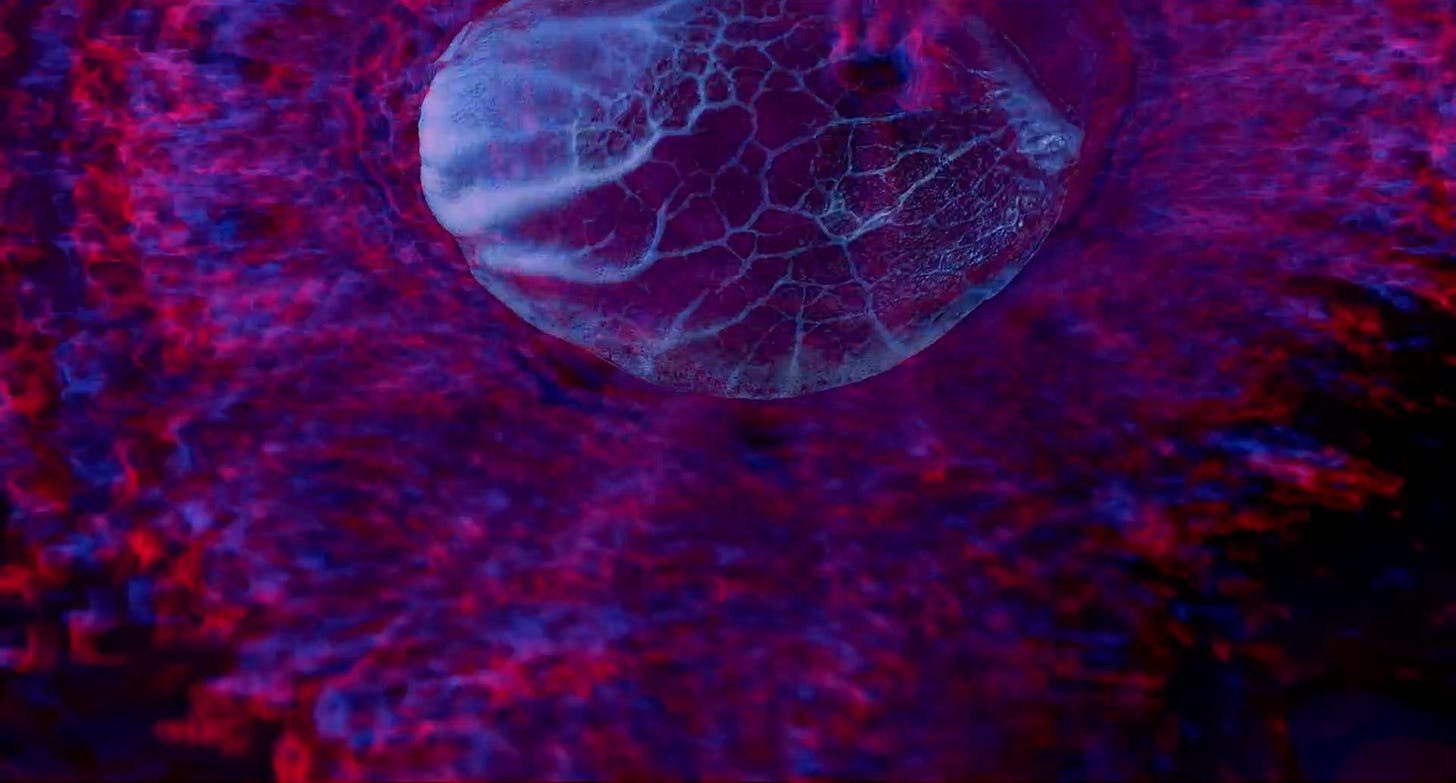

The other short, Brian Zahm’s Photosynthesis, was just screened at Ann Arbor, and uses ChromaDepth glasses, a technology which generates 3D by pulling apart the red and blue colors in images. It’s a recent technology which, like diffraction glasses, has mostly been used to view existing works (especially animations with strong primary colors) through a new lens. The glasses are very cheap, and it’s worth getting them just to view eg Lillian Schwartz or Jordan Belson films. Zahm’s film is a sort of perceptual art experiment which examines plant processes at both a microscopic and macroscopic level, combining animation and photography. Its appeal, for me at least, is largely on the more abstract level of pure aesthetics, as it’s one of extremely few films actually designed in pure red and blues for the ChromaDepth technology, and it looks very good.

The most substantial of the recent 3D films, and my favorite, is Twittering Soul. It’s one of precious few stereoscopic films which lies somewhere between the extremes of commercial features and the avant garde, more in the realm of an arthouse festival narrative. It’s a kind of fantasy, playing on mythologies I’m not very familiar with primarily through suggestive symbolism and dialogue rather than any overtly fantastical images (with the two major exceptions of a mysterious glowing light that appears several times in the background, and a startling departure from realism in the climactic sequence). The film is dryly theatrical, in a way that might feel familiar and even stale except that it very effectively leans into 3D imagery.

What’s most visually striking about the film is that, very unusually for a narrative 3D film, it’s shot almost entirely in wide compositions, often extremely wide landscape shots that frame characters as tiny figures in an expansive view. The stereoscopic depth of the images is therefore primarily in landscapes and architecture rather than human activity, with the result that it often feels like looking at a model train style miniature laid out across a table in front of you. This accomplishes a sort of critical distancing and defamiliarizing effect that many recent festival films aim for, but in a fresh way that never has to overtly break the film’s immersive atmosphere.

The other feature film is Leslie Buchbinder’s Westermann, a documentary about the life and work of the artist H. C. Westermann. It’s quite a strange film. On one level, it works as a fairly standard documentary, with talking head interviews and texts from letters written by Westermann and so on. In that way it’s not very effective. The lineup of interviewees is impressive—Frank Gehry, Terry Allen, Westermann’s family members—but the film doesn’t manage to find an analytical thread that rises above scattered information and commentary. Worse, the artist’s letters are read here by Ed Harris, and it only ever sounds like Ed Harris talking and not an illusion of the artist’s voice. The effect is startling when it repeatedly cuts from live interviews to these reenactment segments, often with animated images of the letters or their text floating above some other image like a bizarre 3D version of a tv documentary.

But like most stereoscopic films, it’s where the film leans into 3D images and gets formally adventurous that it’s most interesting and effective. The film begins with a series of shots of Westermann’s sculptural works, a subject matter that is obviously ripe for this format, and they’re filmed well. The composition really leans into the 3D, which for the sculptures is straightforwardly effective, but at other times has bizarre results. Some of the interviews, for example, frame their subjects across tables which appear massive, the interviewee receding deep into the background. A number of sequences sharply juxtapose flat images—the artist’s letters, photographs, and so on—with 3D ones in a sort of multimedia layering. It’s weird, but for me at least this is much more fascinating viewing that a more dryly conventional doc.

I’m unsure of the extent to which the editing strategy is deliberately strange or accidentally so because of the application of 3D to conventions not meant for it. The former makes sense given the playfully untrained, earnest naivete of Westermann’s work. He would send letters to friends with drawings all over letter and envelope alike, craft elaborate storage containers for six packs of cheap beer, and so on. The film’s eccentricities are more charming, even compelling, if you think of them as a deliberate embrace of this aspect of the Westermann’s work. I definitely don’t think everything works, but there are plenty of delightful surprises and just some cool shit to look at, and I think it’s worth catching a screening if you have the chance.