Three films from Light Field 2023

pài-lak ē-poo (Erica Sheu)

Erica Sheu’s films, most of them less than four minutes long, feel like expressions of singular thoughts or feelings, complex in resonance but extremely focused in material and scope. Her earliest works were diary films, recording the experience of places (the neighborhood around a Chinese funeral house in Take a Walk, the view from a window in Afternoon) and contexts (Sheu’s recent readings about film in First Draft, shared reflections about the meaning of home for two immigrants on a train in The Way Home). Nearly all of the films are inflected with the question of Asian-American experience of history and place.

Sheu began moving in a new direction with Transcript (2019), which retains the interest in processes of recording but moves away from life in NYC and into the studio, filming flowering branches and transcribing their imprints onto photosensitive blue paper. Transcript marked a new level of aesthetic precision, a control of composition and editing that Sheu continues in grandma’s scissors (2021), a reflection on memories of her grandmother, and in her latest work, pài-la̍k ē-poo (saturday afternoon), also dedicated to her grandmother. The film opens with shots of leafy branches framed against the sky, a half-moon visible in the daylight, before cutting to a glass of water set in the grass. It proceeds from there as a study in in changing natural light and color, showing the same flower and glass in direct sunlight and in shadow, the sky at one time a saturated cerulean and at another washed our

These images, beautiful in their apparent simplicity, are given tactile dimension by the film’s use of sound. The first sounds are the crackle of a microphone near closely mic’d flowing water (never shown on screen), giving the audience a sense of physical proximity and the images a place in a world broader than what’s seen. Cuts are marked by pops and the dings of metal on glass, further enhancing this sense of material presence. A sing-songy tune in Japanese plays, suggesting some unknown connection with childhood memory, and the film ends with a hand raising the glass toward the sky before taking a drink, a gesture connecting the heavenly or spiritual realm of aspiration and memory to the grounded reality of the present, and dissolving the difference. pài-la̍k ē-poo is a serene offering made to the memory of a loved one, a presence summoned by shades of light preserved on celluloid.

water, clock (Zack Parrinella)

Zack Parrinella’s films suggest the immanence of forces not immediately perceptible through human senses and memory. They maneuver for a view of what can’t be viewed, through the reworked associations of sound and color in the Color Prism Suite series, the destabilizing rapid camera motions of Interior, the primordial abstractions of Nest Visions. His latest film, water, color, takes up the question of time and relates it to the human quest for immortality through the power of ideas and abstraction.

The film opens with a set of images which appear quickly and vanish into blackness, introducing the visual motifs of water, rock, and industry. “Our eyes form the first circle, the horizon the second, beyond this nature repeats itself,” onscreen text tells us, quoting a Ralph Waldo Emerson essay about how each profane object and perception disappears into greater and greater circles of awareness, approaching an idealist God. As water, clock elaborates its images in a rushing montage which speeds to the point of illegibility, it introduces glimpses of charts and figures representing scientific and technological achievement, and text continues to appear describing our admiration for these feats of the mind and their ephemerality. We drill further into the earth, build higher above it, but the towers and gears of industry will crumble, while the flowing waters of time are permanent.

The film’s final image is a near-Cubist array of fragmented and distorted mirror reflections of glass, metal, and lights, with trees locked up inside. Ironically, though we strive to transcend the inevitability of time and death and to conquer nature, we find ourselves lost in a modernist maze of our own creation, unable to hold onto what little time we have. “We create time from the stars, we mimic time with water.”

Cypris (Marcelle Thirache)

Marcelle Thirache creates visual abstraction from concrete materials, treating light and color and above all texture as painterly elements inherent in the visible world and ready to be captured on the canvas of film. Motion—of the camera, of the surface of water, of light—is her brushstroke. Many of her films are directly inspired by painters, and resemble various movements of modernist art. Impressions (1995), for example, is filmed from out of focus leaves in autumn and resembles impressionist painting, but other works recall Cubism and so on.

Unlike these modernists of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, however, Thirache is not seeking an abstract means of representation in order to capture the distortions and fragmentation of human perception, but conversely is alienating objects from the usual associations and meaning they have for us until they reappear as their purely formal visible elements. In that sense, perhaps her quintessential film is Monet Is Monet (1986), which films the surface of a Monet in macrophotography such that its particular content disappears into the textures of paint, then films the remarkably similar textures of various rocks, stating an equivalence between the two that erases their functional meaning in favor of pure abstraction.

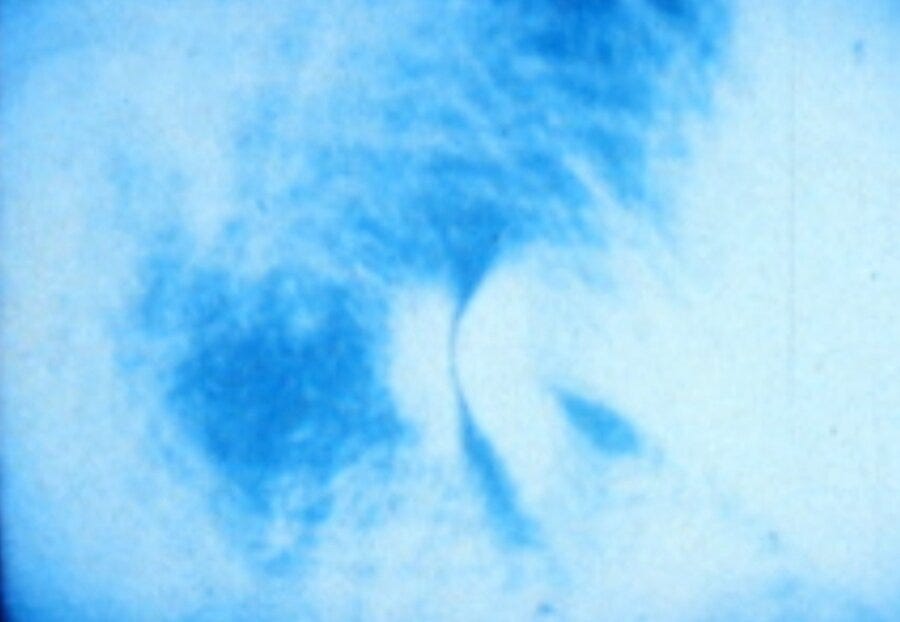

Cypris (1995) is filmed from the surface of a reflective material (it could be a metal or a shiny fabric) illuminated in alternating tones of blue and yellow. The film captures patterns of shifting light and rippling texture, moving slowly at first then accelerating into a quick montage that resembles the late handpainted films of Stan Brakhage. It’s an abstraction of simple beauty which distills the materiality before the camera while withholding its nominal identity: we have only what we can see of the thing, not what we think we know of it. If Monet Is Monet is something of a mission statement, Cypris may be its realization.